By Erin Shaver, Senior Grantwriter at Joining Vision and Action

It’s that time of year—when I find dirt under my fingernails more often than not, my morning routine includes remembering which beds to water, and I’m somewhat tolerantly anticipating the first fruiting blossoms on my plants. For quite a few of us at JVA, myself clearly included, gardening high season is a favorite time of year.

Growth in the homegrown

With the exception of one summer that I moved across the country mid-season, I’ve had some sort of fruit or vegetable garden every year now since 2010. I also started community gardening in 2016, when I obtained a plot at the community garden at my kids’ elementary school.

Of course, my burgeoning commitment to growing at least some of my own food in the summer months is not unique these days. In fact, according to the National Gardening Association (NGA), in 2017, approximately 117 million Americans had gardened in the past 12 months, up from 99 million in 2012. The number of Americans growing food in community gardens rose 200 percent between 2008 and 2016. Today, approximately 35 percent of households in the United States grow food either at home or in a community garden, and millennials are the fastest-growing demographic of new gardeners.

My community garden is a favorite place in the summer. I love seeing what everyone else is growing, talking to other gardeners and dragging my kids along for all of it, hoping to plant the proverbial seed, pun intended, in their own lives and futures.

Where it all began

This is my third summer community gardening. Despite recent progression in the world of community gardening, it’s hardly a new pastime. According to Smithsonian’s Community of Gardens project, the first modern community gardens in the country were started during an economic recession in the 1890s.

Detroit was an early pioneer city to municipally sponsor transformation of vacant lots in the city to be used for gardening. Community gardens’ popularity ebbed and flowed throughout the century that followed—typically, the tighter the economic times, the more interest and funding that flowed to gardens. Throughout each world war, garden movements such as “liberty gardens” and “war gardens” picked up steam, and in the early 20th century, school gardens began appearing in New York City.

During more prosperous times, such as the rise of suburbia in the 1950s, interest waned. The modern environmental movement starting in the 1970s brought urban gardens back to various cities, although it really wasn’t until the last decade or so that urban community gardens became, well, a thing. But the trend seems here to stay.

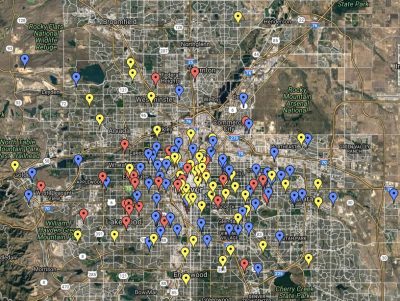

This map is sourced from Denver Urban Gardens. Map markers are reflective of the 2018 season and are color coded as follows: blue is available, yellow is full, and red is not open to public. Learn more at https://dug.org/find-a-garden/.

Gardens as social justice movement

In the last decade, the social/nonprofit sector has started to look at gardens as a way to address food deserts and health inequities and to bring together communities. Denver is no exception. Locally, Denver Urban Gardens lists more than 170 community gardens it is involved with in the metro area, up from 20–30 gardens in the 1990s. New gardens are popping up every year; just this past year I worked with a client in Aurora to start a community garden for refugees and immigrants to grow their own food in what was previously a blighted parking lot off East Colfax.

With many urban gardens, the benefits are beyond simply having some homegrown tomatoes and cucumbers (although they really are the best!). With a short growing season in Colorado, the reality is that most urban gardens can’t produce enough to feed all of their patrons or supplant store-bought items anywhere near entirely. But the benefits beyond fresh, cheap, tasty veggies are far reaching.

A landmark 2016 Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future literature review on the benefits of urban community gardens touted many more societal advantages besides the food. According to the study, urban agriculture’s most significant benefits center on its ability to increase social capital, community wellbeing and civic engagement with the food system. Having a common green space brings the community together and provides equitable access to nutrition and health in areas where fresh food might be scarce. Young and old learn from one another and become more connected to the food system and to one another. Neighborhoods come together, and they might better organize and be engaged on other health and equity issues, or be able to provide for each other in crisis.

Research about the long-term health impacts is sparse but is currently occurring right here in Colorado. CU-Boulder is conducting one of the first-ever randomized controlled trials to explore the measurable health benefits of community gardening. It’s in Year 2 of three of tracking the outcomes for more than 300 Denver Urban Gardens participants to analyze physical and mental health benefits of gardening.

Planting the seed

It’s not too late to jump on the bandwagon. School gardening funding is not quite what it was in the last administration, when Michelle Obama’s campaign included significant support for school and community gardens. But as a grantwriter, I still see numerous grants for gardens every month. There’s Great Outdoors Colorado, which funded turning an old blighted parking lot into a beautiful community/school garden at my own kids’ school and has numerous opportunities throughout the year (schoolyard garden grants are due January 8). There is Colorado Garden Foundation (letter of intent due August 31), and there are national funders such as Whole Foods (due November 15) and Annie’s (typically due in fall), just to name a few.

Or if you’d rather just support organizations doing great work in this space, check out Denver Urban Gardens (supporting over 170 gardens in the metro area), Growing Gardens (supporting gardens and a variety of programs in Boulder County), The Growhaus (co-founded by JVA’s own Adam Brock and providing urban farming and a market in north Denver), Asian Pacific Development Center ($50 supports a family’s garden plot for an entire season) and Slow Food Denver (supporting farmers’ markets, school gardens and other programs in the city)—just for starters! Oh, and Slow Food Nations will be in Denver on July 13–15 for a festival celebrating all things gardening and local. I’ll try to be there. In the interim, though, please don’t mind the dirt under my nails. It’s the season.

Leave A Comment